London Natural History Museum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Natural History Museum in

The foundation of the collection was that of the Ulster doctor Sir

The foundation of the collection was that of the Ulster doctor Sir

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened on 18 April 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883. The museum received both positive and negative reviews by the media upon its opening, but most viewed the museum as a positive contribution to society. In addition to routine maintenance, the building has been altered over the years, especially after it sustained damage in World War II.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened on 18 April 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883. The museum received both positive and negative reviews by the media upon its opening, but most viewed the museum as a positive contribution to society. In addition to routine maintenance, the building has been altered over the years, especially after it sustained damage in World War II.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the

Nature Live

talks on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

*

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

*

The museum runs a series of

The museum runs a series of

Picture Library of the Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum on Google Cultural Institute

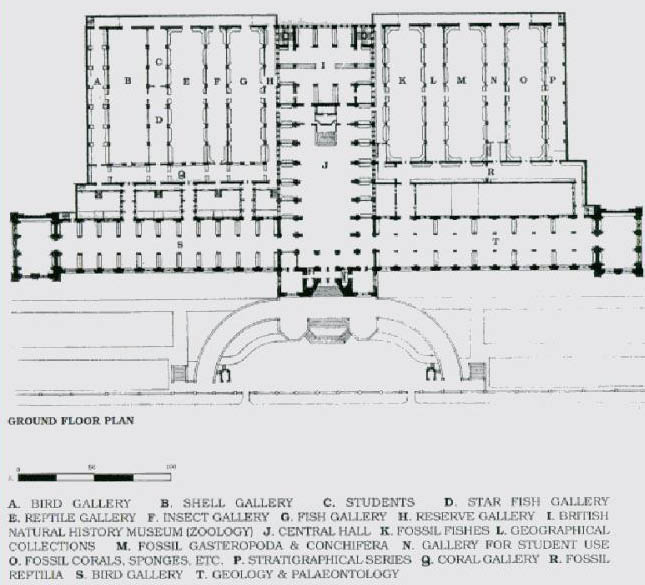

Architectural history and description

from the ''

Architecture and history of the NHM

from the

Nature News article on proposed cuts, June 2010

{{Authority control 1881 establishments in England Alfred Waterhouse buildings British Museum

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road

Exhibition Road is a street in South Kensington, London which is home to several major museums and academic establishments, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum, London, Science Museum and the Natural History Museum, Lon ...

in South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

, the others being the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

and the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

. The Natural History Museum's main frontage, however, is on Cromwell Road

Cromwell Road is a major London road in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, designated as part of the A4 road (Great Britain), A4. It was created in the 19th century and is said to be named after Richard Cromwell, son of Oliver Cromwel ...

.

The museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

, mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

, palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

and zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

. The museum is a centre of research specialising in taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

, identification and conservation. Given the age of the institution, many of the collections have great historical as well as scientific value, such as specimens collected by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

. The museum is particularly famous for its exhibition of dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

skeletons and ornate architecture—sometimes dubbed a ''cathedral of nature''—both exemplified by the large ''Diplodocus

''Diplodocus'' (, , or ) is an extinct genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaurs known from the Late Jurassic of North America. The first fossils of ''Diplodocus'' were discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othnie ...

'' cast

Cast may refer to:

Music

* Cast (band), an English alternative rock band

* Cast (Mexican band), a progressive Mexican rock band

* The Cast, a Scottish musical duo: Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis

* ''Cast'', a 2012 album by Trespassers William ...

that dominated the vaulted central hall before it was replaced in 2017 with the skeleton of a blue whale hanging from the ceiling. The Natural History Museum Library contains an extensive collection of books, journals, manuscripts, and artwork linked to the work and research of the scientific departments; access to the library is by appointment only. The museum is recognised as the pre-eminent centre of natural history and research of related fields in the world.

Although commonly referred to as the Natural History Museum, it was officially known as British Museum (Natural History) until 1992, despite legal separation from the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

itself in 1963. Originating from collections within the British Museum, the landmark Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known for his designs ...

building was built and opened by 1881 and later incorporated the Geological Museum

The Geological Museum (originally the Museum of Economic Geology then the Museum of Practical Geology) was a museum of geology in London. It started in 1835, making it one of the oldest public single science collections in the world. It transfe ...

. The Darwin Centre is a more recent addition, partly designed as a modern facility for storing the valuable collections.

Like other publicly funded national museums in the United Kingdom, the Natural History Museum does not charge an admission fee.

The museum is an exempt charity An exempt charity is an institution established in England and Wales for charitable purposes which is exempt from registration with, and oversight by, the Charity Commission for England and Wales.

Exempt charities are largely institutions of furt ...

and a non-departmental public body

In the United Kingdom, non-departmental public body (NDPB) is a classification applied by the Cabinet Office, Treasury, the Scottish Government, and the Northern Ireland Executive to public sector organisations that have a role in the process o ...

sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) is a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, ministerial department of the Government of the United Kingdom. It holds the responsibility for Culture of the United Kingdom, culture a ...

. The Princess of Wales is a patron of the museum. There are approximately 850 staff at the museum. The two largest strategic groups are the Public Engagement Group and Science Group.

History

Early history

Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector. He had a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British ...

(1660–1753), who allowed his significant collections to be purchased by the British Government at a price well below their market value at the time. This purchase was funded by a lottery. Sloane's collection, which included dried plants, and animal and human skeletons, was initially housed in Montagu House, Bloomsbury, in 1756, which was the home of the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

.

Most of the Sloane collection had disappeared by the early decades of the nineteenth century. Dr George Shaw (Keeper of Natural History 1806–1813) sold many specimens to the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

and had periodic ''cremations'' of material in the grounds of the museum. His successors also applied to the trustees for permission to destroy decayed specimens. In 1833, the Annual Report states that, of the 5,500 insects listed in the Sloane catalogue, none remained. The inability of the natural history departments to conserve its specimens became notorious: the Treasury refused to entrust it with specimens collected at the government's expense. Appointments of staff were bedevilled by gentlemanly favouritism; in 1862 a nephew of the mistress of a Trustee was appointed Entomological Assistant despite not knowing the difference between a butterfly and a moth.

J. E. Gray (Keeper of Zoology 1840–1874) complained of the incidence of mental illness amongst staff: George Shaw threatened to put his foot on any shell not in the 12th edition

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number, numeral, and glyph. It is the first and smallest positive integer of the infinite sequence of natural numbers. This fundamental property has led to its unique uses in other fields, ranging from science to sp ...

of Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

' ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the Orthographic ligature, ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Sweden, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the syste ...

''; another had removed all the labels and registration numbers from entomological

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the ...

cases arranged by a rival. The huge collection of the conchologist

Conchology, from Ancient Greek κόγχος (''kónkhos''), meaning "cockle (bivalve), cockle", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is the study of mollusc shells. Conchology is one aspect of malacology, the study of mollus ...

Hugh Cuming

Hugh Cuming (14 February 1791 – 10 August 1865) was an English collector who was interested in natural history, particularly in conchology and botany. He has been described as the "Prince of Collectors".

Born in England, he spent a number of ...

was acquired by the museum, and Gray's own wife had carried the open trays across the courtyard in a gale: all the labels blew away. That collection is said never to have recovered.

The Principal Librarian at the time was Antonio Panizzi

Sir Antonio Genesio Maria Panizzi (16 September 1797 – 8 April 1879), better known as Anthony Panizzi, was a naturalised British citizen of Italian birth, and an Italian patriot. He was a librarian, becoming the Principal Librarian (i.e. hea ...

; his contempt for the natural history departments and for science in general was total. The general public was not encouraged to visit the museum's natural history exhibits. In 1835 to a Select Committee of Parliament, Sir Henry Ellis said this policy was fully approved by the Principal Librarian and his senior colleagues.

Many of these faults were corrected by the palaeontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, appointed Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum in 1856. His changes led Bill Bryson

William McGuire Bryson ( ; born 8 December 1951) is an American-British journalist and author. Bryson has written a number of nonfiction books on topics including travel, the English language, and science. Born in the United States, he has be ...

to write that "by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for".

Planning and architecture of new building

Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. Only thirty-three submissions were made, many of which contained elements of the Renaissance style. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer CaptainFrancis Fowke

Francis Fowke (7 July 1823 – 4 December 1865) was an Irish engineer and architect, and a captain in the Corps of Royal Engineers. Most of his architectural work was executed in the Renaissance style, although he made use of relatively new ...

, who died shortly afterwards in December 1865. To give the project to the second-place winner would have been viewed as disrespectful to Fowke's memory, and instead the decision was made to expand on his original plans. The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known for his designs ...

, who was hired in February 1866, and who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style, which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent. The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. Initially, Waterhouse's approximate cost was £495,000, but after further discussion was revised to £330,000. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre. Waterhouse spent time with those in charge of each department of the museum to learn more about their needs, which helped him clarify his plans before construction began.

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened on 18 April 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883. The museum received both positive and negative reviews by the media upon its opening, but most viewed the museum as a positive contribution to society. In addition to routine maintenance, the building has been altered over the years, especially after it sustained damage in World War II.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened on 18 April 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883. The museum received both positive and negative reviews by the media upon its opening, but most viewed the museum as a positive contribution to society. In addition to routine maintenance, the building has been altered over the years, especially after it sustained damage in World War II.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta

Architectural terracotta refers to a fired mixture of clay and water that can be used in a non-structural, semi-structural, or structural capacity on the exterior or interior of a building. Terracotta is an ancient building material that transla ...

tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literatur ...

London, manufactured by the Tamworth-based company of Gibbs and Canning. The tiles and bricks feature many relief sculptures of flora and fauna, with living and extinct species featured within the west and east wings respectively. This explicit separation was at the request of Owen, and has been seen as a statement of his contemporary rebuttal of Darwin's attempt to link present species with past through the theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

. Though Waterhouse slipped in a few anomalies, such as bats amongst the extinct animals and a fossil ammonite with the living species. The sculptures were produced from clay models by a French sculptor based in London, M Dujardin, working to drawings prepared by the architect.

The central axis of the museum is aligned with the tower of Imperial College London

Imperial College London, also known as Imperial, is a Public university, public research university in London, England. Its history began with Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, who envisioned a Al ...

(formerly the Imperial Institute) and the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

and Albert Memorial

The Albert Memorial is a Gothic Revival Ciborium (architecture), ciborium in Kensington Gardens, London, designed and dedicated to the memory of Albert, Prince Consort, Prince Albert of Great Britain. Located directly north of the Royal Albert Ha ...

further north. These all form part of the complex known colloquially as Albertopolis

Albertopolis is the nickname given to the area centred on Exhibition Road in London, named after Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria. It contains many educational and cultural sites. It lies in the former village of Brompton in Middlesex ...

.

Separation from the British Museum

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the scientific literature

Scientific literature encompasses a vast body of academic papers that spans various disciplines within the natural and social sciences. It primarily consists of academic papers that present original empirical research and theoretical ...

as ''B.M.(N.H.)''. A petition to the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

was made in 1866, signed by the heads of the Royal

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family or Royalty (disambiguation), royalty

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Ill ...

, Linnean and Zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

societies as well as naturalists including Darwin, Wallace and Huxley, asking that the museum gain independence from the board of the British Museum, and heated discussions on the matter continued for nearly one hundred years. Finally, with the passing of the British Museum Act 1963, the British Museum (Natural History) became an independent museum with its own board of trustees, although – despite a proposed amendment to the act in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

– the former name was retained. In 1989 the museum publicly re-branded itself as the Natural History Museum and stopped using the title British Museum (Natural History) on its advertising and its books for general readers. Only with the Museums and Galleries Act 1992

The Museums and Galleries Act 1992 (c. 44) is an Act of Parliament, act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom the long title of which is "An Act to establish Boards of Trustees of the National Gallery, London, National Gallery, the Tate Gallery ...

did the museum's formal title finally change to the Natural History Museum.

Geological Museum

In 1985, the museum merged with the adjacentGeological Museum

The Geological Museum (originally the Museum of Economic Geology then the Museum of Practical Geology) was a museum of geology in London. It started in 1835, making it one of the oldest public single science collections in the world. It transfe ...

of the British Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance Earth science, geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research. ...

, which had long competed for the limited space available in the area. The Geological Museum became world-famous for exhibitions including an active volcano model and an earthquake machine (designed by James Gardner), and housed the world's first computer-enhanced exhibition (''Treasures of the Earth''). The museum's galleries were completely rebuilt and relaunched in 1996 as ''The Earth Galleries'', with the other exhibitions in the Waterhouse building retitled ''The Life Galleries''. The Natural History Museum's own mineralogy displays remain largely unchanged as an example of the 19th-century display techniques of the Waterhouse building.

The central atrium design by Neal Potter overcame visitors' reluctance to visit the upper galleries by "pulling" them through a model of the Earth made up of random plates on an escalator. The new design covered the walls in recycled slate and sandblasted the major stars and planets onto the wall. The museum's 'star' geological exhibits are displayed within the walls. Six iconic figures were the backdrop to discussing how previous generations have viewed Earth. These were later removed to make place for a ''Stegosaurus

''Stegosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of herbivorous, four-legged, armored dinosaur from the Late Jurassic, characterized by the distinctive kite-shaped upright plates along their backs and spikes on their tails. Fossils of the genus have been fo ...

'' skeleton that was put on display in late 2015.

The Darwin Centre

The Darwin Centre (named afterCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

) was designed as a new home for the museum's collection of tens of millions of preserved specimens, as well as new work spaces for the museum's scientific staff and new educational visitor experiences. Built in two distinct phases, with two new buildings adjacent to the main Waterhouse building, it is the most significant new development project in the museum's history.

Phase one of the Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2002, and it houses the zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

department's 'spirit collections'—organisms preserved in alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

. Phase Two was unveiled in September 2008 and opened to the general public in September 2009. It was designed by the Danish architecture practice C. F. Møller Architects in the shape of a giant, eight-story cocoon and houses the entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

and botanical

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

collections—the 'dry collections'. It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily.

Arguably the most famous creature in the centre is the 8.62-metre-long giant squid

The giant squid (''Architeuthis dux'') is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, ...

, affectionately named Archie.

The Attenborough Studio

As part of the museum's remit to communicate science education and conservation work, a new multimedia studio forms an important part of Darwin Centre Phase 2. In collaboration with the BBC's Natural History Unit (holder of the largest archive of natural history footage) the Attenborough Studio—named after the broadcaster SirDavid Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and writer. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Studios Natural History Unit, the nine nature d ...

—provides a multimedia environment for educational events. The studio holds regular lectures and demonstrations, including freNature Live

talks on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Major specimens and exhibits

One of the most famous and certainly most prominent of the exhibits—nicknamed " Dippy"—is a -long replica of a '' Diplodocus carnegii'' skeleton which was on display for many years within the central hall. The cast was given as a gift by the Scottish-American industrialistAndrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

, after a discussion with King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

, then a keen trustee of the British Museum. Carnegie paid £2,000 () for the casting, copying the original held at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as CMNH) is a natural history museum in the Oakland (Pittsburgh), Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was founded by List of people from the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, Pit ...

. The pieces were sent to London in 36 crates, and on 12 May 1905, the exhibit was unveiled to great public and media interest. The real fossil had yet to be mounted, as the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh was still being constructed to house it. As word of Dippy spread, Mr Carnegie paid to have additional copies made for display in most major European capitals and in Central and South America, making Dippy the most-viewed dinosaur skeleton in the world. The dinosaur quickly became an iconic representation of the museum, and has featured in many cartoons and other media, including the 1975 Disney comedy ''One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing

''One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing'' is a 1975 comedy film set in the early 1920s, about the theft of a dinosaur skeleton from the Natural History Museum. The film was produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by Buena Vista Distributi ...

''. After 112 years on display at the museum, the dinosaur replica was removed in early 2017 to be replaced by the actual skeleton of a young blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

, a 128-year-old skeleton nicknamed "Hope

Hope is an optimistic state of mind that is based on an expectation of positive outcomes with respect to events and circumstances in one's own life, or the world at large.

As a verb, Merriam-Webster defines ''hope'' as "to expect with confid ...

". Dippy went on a tour of various British museums starting in 2018 and concluding in 2020 at Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Norwich, Norfolk, England. The cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Norwich and the mother church of the dioc ...

.

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an urban myth

Urban legend (sometimes modern legend, urban myth, or simply legend) is a genre of folklore concerning stories about an unusual (usually scary) or humorous event that many people believe to be true but largely are not.

These legends can be e ...

that a time capsule

A time capsule is a historic treasure trove, cache of goods or information, usually intended as a deliberate method of communication with future people, and to help future archaeologists, anthropologists, or historians. The preservation of holy ...

was left inside. The work was completed—entirely within the hall and in view of the public—in 1938. At the time it was the largest such model in the world, at in length. The construction details were later borrowed by several American museums, who scaled the plans further. The work involved in removing Dippy and replacing it with Hope was documented in a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

Television special, ''Horizon

The horizon is the apparent curve that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This curve divides all viewing directions based on whethe ...

: Dippy and the Whale'', narrated by David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and writer. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Studios Natural History Unit, the nine nature d ...

, which was first broadcast on BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's second flagship channel, and it covers a wide range of subject matte ...

on 13 July 2017, the day before Hope was unveiled for public display.

The Darwin Centre is host to Archie, an 8.62-metre-long giant squid

The giant squid (''Architeuthis dux'') is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, ...

taken alive in a fishing net near the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

in 2004. The squid is not on general display, but stored in the large tank room in the basement of the Phase 1 building. It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items behind the scenes for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily. On arrival at the museum, the specimen was immediately frozen while preparations commenced for its permanent storage. Since few complete and reasonably fresh examples of the species exist, "wet storage" was chosen, leaving the squid undissected. A 9.45-metre acrylic tank was constructed (by the same team that provide tanks to Damien Hirst

Damien Steven Hirst (; né Brennan; born 7 June 1965) is an English artist and art collector. He was one of the Young British Artists (YBAs) who dominated the art scene in the UK during the 1990s. He is reportedly the United Kingdom's richest ...

), and the body preserved using a mixture of formalin

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is an organic compound with the chemical formula and structure , more precisely . The compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde. It is stored as ...

and saline solution

Saline (also known as saline solution) is a mixture of sodium chloride (salt) and water. It has a number of uses in medicine including cleaning wounds, removal and storage of contact lenses, and help with dry eyes. By injection into a vein, i ...

.

The museum holds the remains and bones of the "River Thames whale

The River Thames whale, affectionately nicknamed Willy by Londoners, was a juvenile female northern bottlenose whale which was discovered swimming in the River Thames in central London on Friday 20 January 2006. According to the BBC, she was fi ...

", a northern bottlenose whale

The northern bottlenose whale (''Hyperoodon ampullatus'') is a species of beaked whale in the ziphiid family, being one of two members of the genus '' Hyperoodon''. The northern bottlenose whale was hunted heavily by Norway and Britain in the 1 ...

that lost its way on 20 January 2006 and swam into the Thames. Although primarily used for research purposes, and held at the museum's storage site at Wandsworth

Wandsworth Town () is a district of south London, within the London Borough of Wandsworth southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

Toponymy

Wandsworth takes its name ...

.

'' Dinocochlea'', one of the longer-standing mysteries of paleontology (originally thought to be a giant gastropod shell

The gastropod shell is part of the body of many gastropods, including snails, a kind of mollusc. The shell is an exoskeleton, which protects from predators, mechanical damage, and dehydration, but also serves for muscle attachment and calcium ...

, then a coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

, and now a concretion

A concretion is a hard and compact mass formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes a ...

of a worm's tunnel), has been part of the collection since its discovery in 1921.

The museum keeps a wildlife garden on its west lawn, on which a potentially new species of insect resembling '' Arocatus roeselii'' was discovered in 2007.

Galleries

The museum is divided into four sets of galleries, or zones, each colour coded to follow a broad theme.Red Zone

This is the zone that can be entered from Exhibition Road, on the East side of the building. It is a gallery themed around the changing history of the Earth. ''Earth's Treasury'' shows specimens of rocks, minerals and gemstones behind glass in a dimly lit gallery. ''Lasting Impressions'' is a small gallery containing specimens of rocks, plants and minerals, of which most can be touched. * Earth Hall (''Stegosaurus

''Stegosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of herbivorous, four-legged, armored dinosaur from the Late Jurassic, characterized by the distinctive kite-shaped upright plates along their backs and spikes on their tails. Fossils of the genus have been fo ...

'' skeleton)

* Human Evolution

* Earth's Treasury

* Lasting Impressions

* Restless Surface

* From the Beginning

* Volcanoes and Earthquakes

* The Waterhouse Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

Green zone

This zone is accessed from the Cromwell Road entrance via the Hintze Hall and follows the theme of the evolution of the planet. * Birds * Creepy Crawlies * Fossil Way (marine reptiles, a giant sloth, and the Swindon stegosaur '' Dacentrurus'') * Hintze Hall (formerly the Central Hall, withblue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

skeleton and giant sequoia

''Sequoiadendron giganteum'' (also known as the giant sequoia, giant redwood, Sierra redwood or Wellingtonia) is a species of coniferous tree, classified in the family Cupressaceae in the subfamily Sequoioideae. Giant sequoia specimens are the la ...

)

* Minerals

* The Vault

* Fossils from the UK

* Anning Rooms (exclusive space for members and patrons of the museum)

* Investigate

* East Pavilion (space for changing Wildlife Photographer of the Year exhibition)

Blue zone

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

*

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

* Dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s

* Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles

* Human Biology

* Images of Nature

* The Jerwood Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

* Marine Invertebrates

* Mammals

* Mammals Hall (blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

model)

* Treasures in the Cadogan Gallery

Orange zone

Enables the public to see science at work and also provides spaces for relaxation and contemplation. Accessible from Queens Gate. * Wildlife Garden * Darwin Centre * Zoology Spirit BuildingHighlights of the collection

* Otumpairon meteorite

Iron meteorites, also called siderites or ferrous meteorites, are a type of meteorite that consist overwhelmingly of an iron–nickel alloy known as meteoric iron that usually consists of two mineral phases: kamacite and taenite. Most iron me ...

weighing , found in 1783 in Campo del Cielo

Campo del Cielo ("Field of Heaven" or "Field of the Sky" in English) refers to a group of iron meteorites and the area in Argentina where they were found. The site straddles the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero, located north-northwes ...

, Argentina

* Fragments of the Nakhla meteorite

Nakhla is a Martian meteorite which fell in Egypt in 1911. It was the first meteorite reported from Egypt, the first one to suggest signs of aqueous processes on Mars, and the prototype for Nakhlite type of meteorites.

History

The Nakhla me ...

from Egypt, the first meteorite to suggest signs of aqueous processes on Mars

* Latrobe nugget, one of the largest known clusters of cubic gold crystals

* Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth human spaceflight, crewed mission in the United States Apollo program, Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to Moon landing, land on the Moon. It was the second o ...

Moon rock sample collected in 1972

* Ostro Stone, flawless blue topaz

Topaz is a silicate mineral made of aluminium, aluminum and fluorine with the chemical formula aluminium, Alsilicon, Sioxygen, O(fluorine, F, hydroxide, OH). It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural ...

gemstone weighing 9,381 carats, about , the largest of its kind in the world

* Aurora Pyramid of Hope, a collection of 296 natural diamonds in a wide variety of colours

* First complete ichthyosaur skull ever discovered (discovered by Joseph Anning in 1811)

* First complete skeleton of a plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

ever discovered (discovered by Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

in 1823)

* The plesiosaur '' Attenborosaurus'' named after David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and writer. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Studios Natural History Unit, the nine nature d ...

* Cast of a huge skeleton of ''Rhomaleosaurus

''Rhomaleosaurus'' (meaning "strong lizard") is an extinct genus of Early Jurassic (Toarcian Faunal stage, age, about 183 to 175.6 million years ago) rhomaleosaurid pliosauroid known from Northamptonshire and from Yorkshire of the United Kingdom. ...

''

* First ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species found worldwide have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Taxonomy (bi ...

'' teeth ever discovered

* Near complete skeleton of ''Mantellisaurus

''Mantellisaurus'' is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur that lived in the Barremian and early Aptian ages of the Early Cretaceous Period of Europe. Its remains are known from Belgium (Bernissart), England, Spain and Germany. The type species, ty ...

''

* The most intact ''Stegosaurus

''Stegosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of herbivorous, four-legged, armored dinosaur from the Late Jurassic, characterized by the distinctive kite-shaped upright plates along their backs and spikes on their tails. Fossils of the genus have been fo ...

'' fossil skeleton ever discovered (nicknamed Sophie)

* Large skull of a ''Triceratops

''Triceratops'' ( ; ) is a genus of Chasmosaurinae, chasmosaurine Ceratopsia, ceratopsian dinosaur that lived during the late Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous Period (geology), period, about 68 to 66 million years ago on the island ...

''

* Skeleton of ''Baryonyx

''Baryonyx'' () is a genus of theropod dinosaur which lived in the Barremian stage of the Early Cretaceous period, about 130–125 million years ago. The first skeleton was discovered in 1983 in the Smokejack Clay Pit, of Surrey, England, in ...

''

* Full-sized animatronic model of a ''Tyrannosaurus rex

''Tyrannosaurus'' () is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' ( meaning 'king' in Latin), often shortened to ''T. rex'' or colloquially t-rex, is one of the best represented theropods. It live ...

''

* First specimen of ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird'') is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaîos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'' ever discovered, one of only 14 found and generally accepted by palaeontologists to be the oldest known bird

* Rare dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

skeleton, reconstructed from bones over 1,000 years old

* Only surviving specimen of the Great Auk

The great auk (''Pinguinus impennis''), also known as the penguin or garefowl, is an Extinction, extinct species of flightless bird, flightless auk, alcid that first appeared around 400,000 years ago and Bird extinction, became extinct in the ...

from the British Isles, collected in 1813 from Papa Westray

Papa Westray () (), also known as Papay, is one of the Orkney Islands in Scotland, United Kingdom. The fertile soilKeay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) ''Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland''. London. HarperCollins. has long been a draw to the island.

...

in the Orkney Islands

* A complete skeleton of an American mastodon

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

* Broken Hill skull, Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle P ...

cranium

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

now considered part of a ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' is a species of archaic human from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Africa, as well as potentially Asia depending on the taxonomic convention used. The species-level classification of ''Homo'' during the Middle Pleis ...

'', discovered in the mine of Broken Hill or Kabwe

Kabwe is the capital of the Zambian Central Province and the Kabwe District, with a population estimated at 288,598 at the 2022 census. Named Broken Hill until 1966, it was founded when lead and zinc deposits were discovered in 1902. Kabwe also ...

in Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

* Gibraltar 1 and Gibraltar 2, two Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

skulls found at Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

* Cross-section of 1,300-year-old giant sequoia

''Sequoiadendron giganteum'' (also known as the giant sequoia, giant redwood, Sierra redwood or Wellingtonia) is a species of coniferous tree, classified in the family Cupressaceae in the subfamily Sequoioideae. Giant sequoia specimens are the la ...

, at the museum since 1893

* Rare copy of ''The Birds of America

''The Birds of America'' is a book by naturalist and painter John James Audubon, containing illustrations of a wide variety of birds of the United States. It was first published as a series in sections between 1827 and 1838, in Edinburgh and L ...

'' by John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin, April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American Autodidacticism, self-trained artist, natural history, naturalist, and ornithology, ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornitho ...

, containing illustrations of a wide variety of birds from the United States

* Rare first edition of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''

Education and research

The museum runs a series of

The museum runs a series of educational

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education also fol ...

and public engagement programmes. These include for example a highly praised "How Science Works" hands on workshop for school students demonstrating the use of microfossils in geological research. The museum also played a major role in securing designation of the Jurassic Coast

The Jurassic Coast, also known as the Dorset and East Devon Coast, is a World Heritage Site on the English Channel coast of southern England. It stretches from Exmouth in East Devon to Studland Bay in Dorset, a distance of about , and was ins ...

of Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

and Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

and has subsequently been a lead partner in the Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

Fossil Festivals.

In 2005, the museum launched a project to develop notable gallery characters to patrol display cases, including 'facsimiles' of Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

, Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

, Dorothea Bate

Dorothea Minola Alice Bate (8 November 1878 – 13 January 1951), also known as Dorothy Bate, was a Welsh palaeontologist and pioneer of archaeozoology. Her life's work was to find fossils of recently extinct mammals with a view to understandi ...

and William Smith William, Willie, Will, Bill, or Billy Smith may refer to:

Academics

* William Smith (Master of Clare College, Cambridge) (1556–1615), English academic

* William Smith (antiquary) (c. 1653–1735), English antiquary and historian of University C ...

. They tell stories and anecdotes of their lives and discoveries and aim to surprise visitors.

In 2010, a six-part BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

documentary series was filmed at the museum entitled ''Museum of Life

The Museum of Life is located at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-mo ...

'' exploring the history and behind the scenes aspects of the museum.

Since May 2001, the Natural History Museum admission has been free for some events and permanent exhibitions. However, there are certain temporary exhibits and shows that require a fee.

The Natural History museum combines the museum's life and earth science collections with specialist expertise in "taxonomy, systematics, biodiversity, natural resources, planetary science, evolution and informatics" to tackle scientific questions.

In 2011, the museum led the setting up of an International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

Bumblebee Specialist Group, chaired by Dr. Paul H. Williams, to assess the threat status of bumblebee

A bumblebee (or bumble bee, bumble-bee, or humble-bee) is any of over 250 species in the genus ''Bombus'', part of Apidae, one of the bee families. This genus is the only Extant taxon, extant group in the tribe Bombini, though a few extinct r ...

species worldwide using Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological sp ...

criteria.

Access

The closestLondon Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

station is South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

— there is a tunnel from the station that emerges close to the entrances of all three museums. Admission to the museum is free, though there are donation boxes in the foyer.

Museum Lane immediately to the north provides disabled access to the museum.

A connecting bridge between the Natural History and Science museums closed to the public in the late 1990s.

In popular culture

The museum plays an important role in the 1975 London-basedDisney

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Di ...

live-action feature ''One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing

''One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing'' is a 1975 comedy film set in the early 1920s, about the theft of a dinosaur skeleton from the Natural History Museum. The film was produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by Buena Vista Distributi ...

''; the eponymous skeleton is stolen from the museum, and a group of intrepid nannies

A nanny is a person who provides child care. Typically, this care is given within the children's family setting. Throughout history, nannies were usually servants in large households and reported directly to the lady of the house. Today, modern ...

hide inside the mouth of the museum's blue whale model (in fact a specially created prop – the nannies peer out from behind the whale's teeth, but a blue whale is a baleen whale

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

and has no teeth). Additionally, the film is set in the 1920s, before the blue whale model was built.

The museum was featured in the 2006 music video for the song, " Friday Night" by McFly

McFly are a British pop rock band formed in London in 2003. The band took their name from the ''Back to the Future (franchise), Back to the Future'' character Marty McFly. The band consists of Tom Fletcher (lead vocals, guitar, and piano), Da ...

, from the soundtrack to the movie, ''Night at the Museum

''Night at the Museum'' is a 2006 fantasy comedy film directed by Shawn Levy and written by Robert Ben Garant and Thomas Lennon. It is based on the 1993 children's book of the same name by Croatian illustrator Milan Trenc. The film had an en ...

''. The video, shot with various handheld cameras, features the band members as security guards at the museum, and then running around London.

The museum features as a base for Prodigium, a secret society

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ag ...

which studies and fights monsters, first appearing on '.

In the 2014 film ''Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

'', Millicent Clyde (played by Nicole Kidman

Nicole Mary Kidman (born 20 June 1967) is an Australian and American actress and producer. Known for Nicole Kidman on screen and stage, her work in film and television productions across many genres, she has consistently ranked among the world ...

) is a devious and treacherous taxidermist at the museum. She kidnaps Paddington, intending to kill and stuff him, but is thwarted by the Brown family after scenes involving chases inside and on the roof of the building.

The museum was prominently featured in the Sky One

Sky One was a British pay television channel operated and owned by Sky Group (a division of Comcast). Originally launched on 26 April 1982 as Satellite Television, it was Europe's first satellite and non- terrestrial channel. From 31 July 1989, ...

2014 documentary David Attenborough's Natural History Museum Alive where several extinct creatures exhibited at the museum including '' Dippy'' the ''Diplodocus'' were brought to life using CGI.

The museum features prominently in the level Lud's Gate from Tomb Raider III

''Tomb Raider III'' (also known as ''Tomb Raider III: Adventures of Lara Croft'') is an action-adventure video game developed by Core Design and published by Eidos Interactive. It was released for the PlayStation and Microsoft Windows platform ...

, with Core Design

Core Design Limited (known as Rebellion (Derby) Ltd between 2006 and 2010) was a British video game developer based in Derby. Founded in May 1988 by former Gremlin Graphics employees, it originally bore the name Megabrite until rebranding as Co ...

launching the game with Jonathan Ross

Jonathan Stephen Ross (born 17 November 1960) is an English broadcaster, film critic, comedian, actor, writer, and producer. He presented the BBC One chat show '' Friday Night with Jonathan Ross'' during the 2000s and early 2010s, hosted his ow ...

at the museum on 15 October 1998.

Andy Day

Andrew Paul Day is an English actor and television presenter. He is best known for his work on the BBC's CBeebies channel. He is also a patron of Anti-Bullying Week.

He was first on Friendly TV in 2005 and moved to CBeebies in 2007, becoming t ...

's CBeebies

CBeebies is a British free-to-air Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast children's television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is also the brand used for all BBC content targeted for children aged six year ...

shows, ''Andy's Dinosaur Adventures'' and ''Andy's Prehistoric Adventures'' are filmed in the Natural History Museum.

The museum was site of the first Pit Stop

Pitstop may refer to:

* Pit stop, in motor racing, when the car stops in the pits for fuel and other consumables to be renewed or replenished

* ''Pit Stop'' (1969 film), a movie directed by Jack Hill

* ''Pit Stop'' (2013 film), a movie directe ...

on '' The Amazing Race 33''.

The museum is featured in the fifth episode of the Apple TV+

Apple TV+ is an American subscription over-the-top streaming service owned by Apple. The service launched on November 1, 2019, and it offers a selection of original production film and television series called Apple Originals. The service w ...

period drama '' The Essex Serpent''.

The museum is featured in the music video for the song "Hordes of Khan", by the Swedish metal band, Sabaton

A sabaton or solleret is part of a knight's body armour, body armor that covers the foot.

History

Sabatons from the 14th and 15th centuries typically end in a tapered point well past the actual toes of the wearer's foot, following poulaines, f ...

. The song is about Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan, was the founder and first khan (title), khan of the Mongol Empire. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongols, Mongol tribes, he launched Mongol invasions and ...

. The video was inspired by ''Night at the Museum''.

Natural History Museum at Tring

The NHM also has an outpost inTring

Tring is a market town and civil parish in the Borough of Dacorum, Hertfordshire, England. It is situated in a gap passing through the Chiltern Hills, classed as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, from Central London.

Tring is linked ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and one of the home counties. It borders Bedfordshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the north-east, Essex to the east, Greater London to the ...

, built by local eccentric Lionel Walter Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoology, zoologist, and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he wa ...

. The NHM took ownership in 1938. In 2007, the museum announced that the name would be changed to the Natural History Museum at Tring, though the older name, the Walter Rothschild Zoological Museum, is still in widespread use.

Move of collections to Harwell and Shinfield

There has been some discussion of plans to move major parts of the collections to sites in Harwell (which was abandoned) and then to Shinfield,Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

. These plans have been heavily criticized, together with the overall departure of the strategic direction of the museum.

See also

* James John Joicey * Keeper of Entomology, Natural History Museum * Sophie the Stegosaurus * :Employees of the Natural History Museum, LondonReferences

Bibliography

* ''DrMartin Lister

Martin Lister (12 April 1639 – 2 February 1712) was an English natural history, naturalist and physician. His daughters Anne Lister (illustrator), Anne and Susanna Lister, Susanna were two of his illustrators and engravers.

J. D. Woodley, 'L ...

: A bibliography

Bibliography (from and ), as a discipline, is traditionally the academic study of books as physical, cultural objects; in this sense, it is also known as bibliology (from ). English author and bibliographer John Carter describes ''bibliograph ...

'' by Geoffrey Keynes

Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes ( ; 25 March 1887, Cambridge – 5 July 1982, Cambridge) was a British surgeon and author. He began his career as a physician in World War I, before becoming a doctor at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, where he ...

. St Paul's Bibliographies (UK). . (Includes illustrations by Lister's wife and daughter).

* ''The Travelling Naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

s'' (1985) by Clare Lloyd. (Study of 18th Century Natural History — includes Charles Waterton

Charles Waterton (3 June 1782 – 27 May 1865) was an English naturalist, plantation overseer and explorer best known for his pioneering work regarding conservation.

Family and religion

Waterton was of a Roman Catholic landed gentry family de ...

, John Hanning Speke

Captain John Hanning Speke (4 May 1827 – 15 September 1864) was an English explorer and army officer who made three exploratory expeditions to Africa. He is most associated with the search for the source of the Nile and was the first Eu ...

, Henry Seebohm

Henry Seebohm (12 July 1832 – 26 November 1895) was an English steel manufacturer, and amateur ornithologist, oologist and traveller.

Biography

Henry was the oldest son of Benjamin Seebohm (1798–1871) who was a wool merchant at Horton G ...

and Mary Kingsley

''For the English novelist, see Mary St Leger Kingsley.''

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (13 October 1862 – 3 June 1900) was an English ethnographer, writer and explorer who made numerous travels through West Africa and wrote several books on ...

). Contains colour and black and white reproductions. Croom Helm (UK). .

* ''Dry storeroom no 1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum'' (2009) by Richard Fortey. HarperPress (UK). .

* ''Nature's Cathedral: A celebration of the Natural History Museum building'' (2020) by John Thackray, Bob Press and Sandra Knapp. Natural History Museum.

External links

*Picture Library of the Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum on Google Cultural Institute

Architectural history and description

from the ''

Survey of London

The Survey of London is a research project to produce a comprehensive architectural survey of central London and its suburbs, or the area formerly administered by the London County Council. It was founded in 1894 by Charles Robert Ashbee, an A ...

''

Architecture and history of the NHM

from the

Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three suppl ...

* Maps of

Nature News article on proposed cuts, June 2010

{{Authority control 1881 establishments in England Alfred Waterhouse buildings British Museum

Natural History Museum, London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum (Lo ...

Charities based in London

Buildings and structures completed in 1880

Dinosaur museums in the United Kingdom

Exempt charities

Grade I listed buildings in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Grade I listed museum buildings

Museums established in 1881

Museums in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Museums sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport

National museums of England

Natural history museums in London

Non-departmental public bodies of the United Kingdom government